CUTANEOUS ROSACEA and dry eye disease have a great deal in common. They both are multifactorial; have inflammatory, autoimmune, and neurological root mechanisms; have possible links to hormones, environment, and microbes, including Demodex mites and bacteria; vary in symptom presentation; and have disease burden/symptom severity that does not always match clinical signs (van Zuuren et al, 2021; Schaller et al, 2020). Both are often underdiagnosed and can be challenging to treat effectively. These conditions overlap when rosacea affects the ocular surface and adnexa in the form of ocular rosacea, which is critical to identify when diagnosing and treating dry eye.

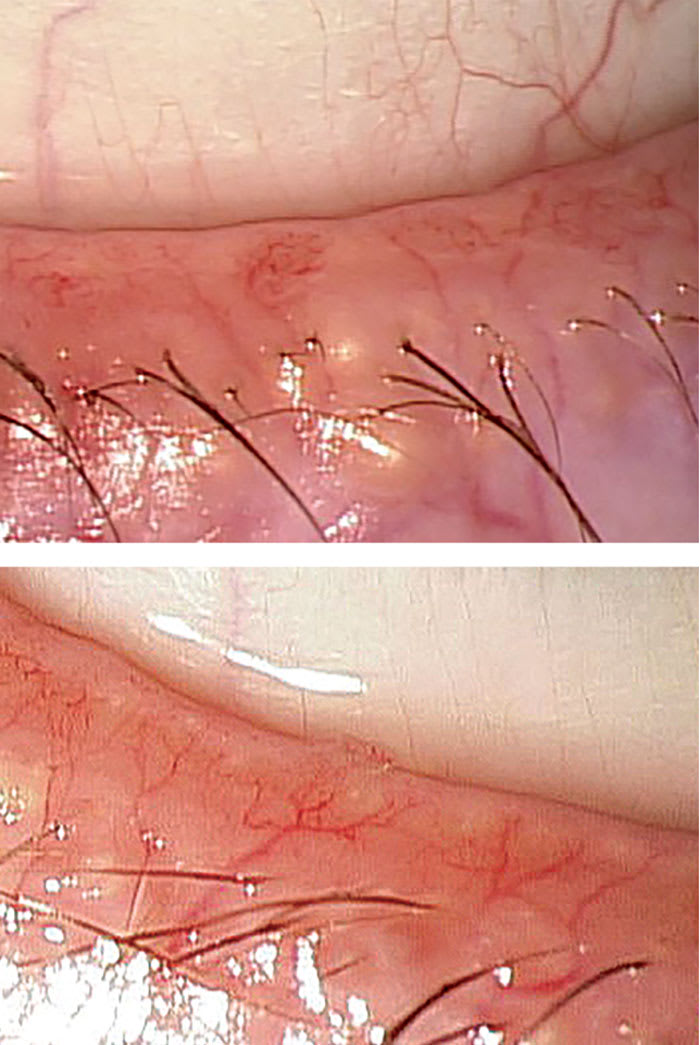

Rosacea was previously compartmentalized into 4 different subtypes: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular. Now, due to significant overlapping of these categories, it is recognized that rosacea should be approached simply based on patient-specific phenotypic expression (Schaller et al, 2020). Diagnostic signs of rosacea include facial erythema, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, vascular abnormalities and telangiectasias, and ocular manifestations (van Zuuren et al, 2021). Ocular features include blepharitis, conjunctivitis, dry eye, meibomian gland dysfunction, lid telangiectasias (Figure 1), and, in severe cases, keratitis, corneal neovascularization, scarring and ulceration, and anterior uveitis (Mohamed-Noriega et al, 2025; Kaur et al, 2023).

Rosacea is estimated to affect 5.5% of the global adult population (although it can also occur in pediatric patients), with ocular rosacea occurring in 10% to 15% of cutaneous cases and also in cases without skin involvement (van Zuuren et al, 2021; Mohamed-Noriega et al, 2025). Rosacea is most often diagnosed in individuals who have fair skin, but it is believed to be widely underdiagnosed in darker skinned populations due to melanin pigment masking of erythromatic and vascular signs (Schaller et al, 2020).

Options for treatment of both ocular and cutaneous rosacea include omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and lifestyle changes like avoidance of triggers (eg, excessive heat, exercise, spicy foods, sunlight/UV exposure, chemical irritants/soaps, and alcohol) (van Zuuren et al, 2021; Mohamed-Noriega et al, 2025). Various topical prescription creams and gels are available for mild facial symptoms, and options for mild ocular involvement include preservative-free artificial tears and lid hygiene (van Zuuren et al, 2021; Mohamed-Noriega et al, 2025).

Moderate to advanced cases may require more aggressive therapy, such as topical immunomodulation for the eyes (cyclosporine, lifitegrast, or steroids), oral antibiotics (doxycycline, minocycline, or azithromycin), or light/thermal therapies (intense pulsed light or thermal pulsation therapy) for both skin and eyelids (Mohamed-Noriega et al, 2025; Zhai et al, 2024; Shergill et al, 2024). ≤

Evidence-based guidelines for initial and maintenance dosing and length of treatment are desperately needed for both oral medication and light-/heat-based therapies, because there is very little current consensus regarding how these should be utilized (Kaur et al, 2023).

Eyecare practitioners should follow developments in the field of dermatologic rosacea closely, because better knowledge of this disease will help in treating related dry eye as well. Collaboration between dermatology and optometry is required to provide relief to patients who are suffering from both skin and ocular symptoms. Eyecare providers must look for facial cues to help diagnose ocular rosacea and should relay their findings to make the dermatologist aware of the patient’s ocular involvement.

References

1. van Zuuren EJ, Arents BWM, van der Linden MMD, Vermeulen S, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J. Rosacea: new concepts in classification and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):457-465. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00595-7

2. Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, et al. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global rosacea consensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1269-1276. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18420

3. Mohamed-Noriega K, Loya-Garcia D, Vera-Duarte GR, et al. Ocular rosacea: an updated review. Cornea.2025;44(4):525-537. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003785

4. Kaur G, Redd TK, Seitzman GD. Practice patterns and clinician opinions for treatment of ocular rosacea. Cornea.2023;42(11):1349-1354. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003157

5. Zhai Q, Cheng S, Liu R, Xie J, Han X, Yu Z. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of intense pulsed light and pulsed-dye laser therapy in the management of rosacea. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2024;23(12):3821-3827. doi: 10.1111/jocd.16549

6. Shergill M, Khaslavsky S, Avraham S, Kashetsky N, Zaslavsky K, Mukovozov I. A review of intense pulsed light in the treatment of ocular rosacea. J Cutan Med Surg. 2024;28(4):370-374. doi: 10.1177/12034754241254051